by Torsten

by Torsten

Pitti Uomo i Florence is a show. Most people dress up, often exaggerating. A main problem is that so much clothes look brand new. You cannot have style in brand new clothes. Impossible. You become a puppet, a clown.

Ready to wear, especially, needs a lot of breaking-in. Bespoke becomes your own swiftly. You don’t have to throw it around like Fred Astaire did, when Anderson & Sheppard had shipped him a new suit. Yet, the point is clear: You & your clothes must be one for style to appear.

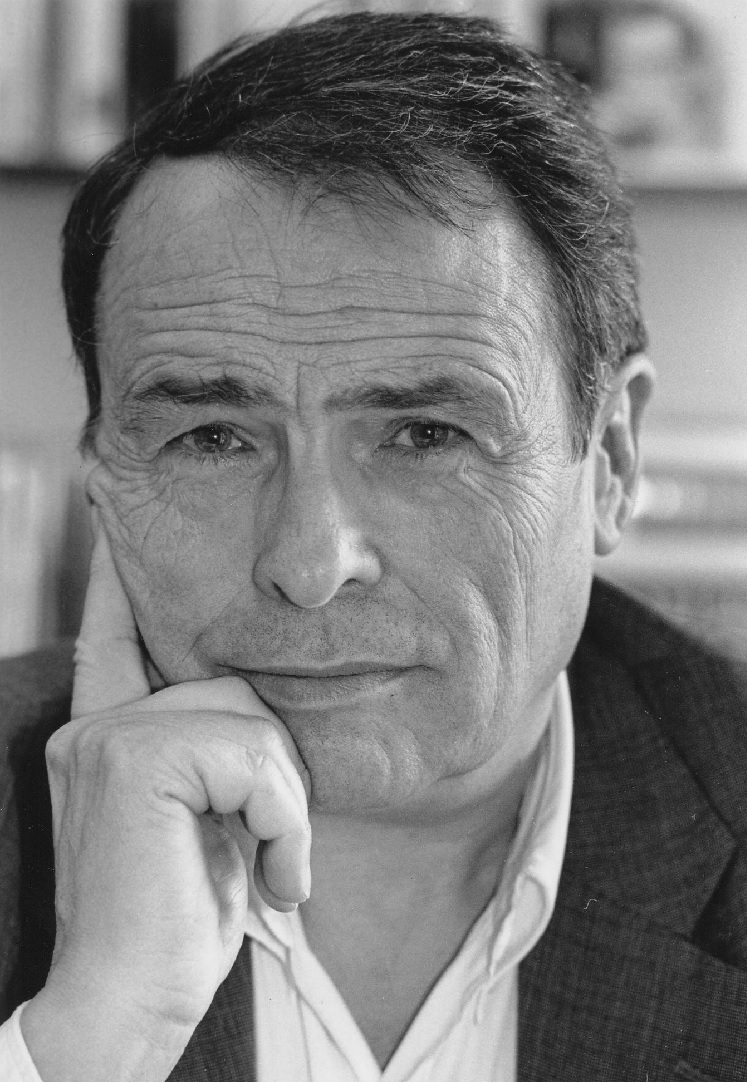

The man in photo was the best dressed I saw at Pitti Uomo 103. Everything about his look is fluent. The colours, the textures, the fit, the tab collar, the tie knot, the watch. He also has strong sense of tradition.

Surely, he is dresses up but effortlessly. There is no friction.

by Torsten

One can look at classic menswear as a set of effects or tools.

The most important tool is fit. Firstly, the clothes must be in spatial harmony with the given body. Dress and man should not conflict physically. Moreover, the fit of the garment must flatter the body, hide imperfections and accentuate assets.

Secondly, you have the textures of the textiles. You must coordinate a tweed jacket with a pair of corduroys or flannel trousers, ordinary worsted trousers do not harmonize with it. One could say that the textures of the individual parts of the garment must be related in terms of warmth and sturdiness, shoes included.

Colours are a third tool. They can contrast more or less harshly. The harsher the contrasts, the more energy an outfit has.

Patterns interact with colours. I usually advice to avoid patterns if the use of colours is contrasting and lively. Conversely, patterns can add energy to a close to monochrome and dull colour scheme.

Design details matter. Flap pockets or jetted pockets, trouser turn-ups or not, single breasted or double breasted. Design details are a fifth tool in a classic attire (along with accessories). Simplicity is not always the right choice. Remember.

by Torsten

The Armour of The Cultured Man

“In the morning, the day we were to leave, I had been dressed as finely as if I were to be photographed, I had been given a new hat and a velvet jacket,” writes Marcel Proust in In Search of Lost Time from the early 1900s.

In his work, velvet or corduroy becomes a noble textile.

Oscar Wilde, his contemporary, also had a weakness for the textile. Wilde wore fancy velvet in protest against the dominant dark garments, he declared.

Later, many other artists, intellectuals, and indeed those with aspirations to be something in the world of culture, were to be attracted to the textile.

Woody Allen uses the symbolic power of corduroy, when he dresses a leading man (and himself) in corduroy. Wes Anderson, who is an auteur like Woody Allen, is also a real velvet man. The textile, whether ribbed or with a plush finish, has become a stylistic signature for him.

As for the photo, I’m wearing slack jacket and trousers from heavy corduroy. On my feet a pair of bespoke Vienna shoes.

by Torsten

Derek from Die, Workwear writes at length about good taste in a recent article. I think I agree with him in several ways. For instance, he’s right that you can hardly define timeless, specific rules in dressing, including classic menswear. Alan Flusser, among others, has a somewhat unfortunate tendency to do so.

But I think Derek uses the sociological arsenal too one-sidedly, so he ends up reducing good taste to a mere act of social desire and positioning. Take Bourdieu, whom Derek uses as an analytical framework. The French sociologist certainly saw taste as a status symbol in class society. But not only. Bourdieu was aware that cultural fields over time develop knowledge and expressions that are not only socially finer than other knowledge and expressions, but may in fact be so. Mahler actually composes better music than Peter in the third grade!

If you take a field like classic menswear, it will also contain, in Bourdieu’s perspective, a real, transhistorical knowledge of dressing well. It is similar to what we call time tested. It could be, for example, colour use and cuts. It is difficult to carve out this knowledge, this good taste, because it is very context-dependent. Many people, like Flusser, get too ambitious here, when they try to specify rules. But anyone who has dealt with a field like classic menswear will recognise that some clothing styles are actually more successful than others, are better taste, because the mastery of basic tools like colours, fabrics and cuts is better. It’s like any other cultural field from theatre to carpentry to a new house. Some things are actually better, more beautiful than others, if you have a knowledge of the field. It is only from a distance that this exercise of taste can look like social positioning alone.

The Norwegian writer Knausgård has captured the experience of good taste in clothes very well:

“Christina always dressed beautifully, not ostentatiously, but unusually tastefully. It was not strange, she was a trained designer. I always looked at her clothes when we met, and it filled me with a kind of pleasure, perhaps it was the accomplished assurance that did it, how everything was coordinated, but without the coordination being visible, for that would have been a demonstration of well-dressing, and how the little details like a scarf or a belt brought out the best in the other parts, like lifted it up, while they themselves were in focus, for example a strong belt buckle, and in the background, as the strong helped to highlight the other. Colours, cuts, fabrics, patterns. Everything was coordinated from a certainty that could not be other than intuitive. It was something she knew how to do, and which she made no effort to create. In this, she was able to do something almost no one can do, which is to blur the differences between what was new and what was used, what was expensive and what was cheap, by disregarding those characteristics and seeing what the clothes or accessories were in themselves.”

Isn’t there a governing principle, a nomos in Bourdieu’s words, even in classic menswear? Yes, tradition/not tradition stands strong. For example, in the field of classic menswear, it is decidedly easier to dress successfully in a blue jacket and white trousers than vice versa, because the former combination is a well-established tradition. In addition, I see that harmony/not harmonious, in straight line from Beau Brummell, influences what is good taste. As a minimum requirement, we can perhaps say that a style in classic menswear must exhibit a tradition-conscious harmony of colors, patterns, fabrics, textures, cuts, make, and accessories in relation to a given body in order to establish itself as good taste.

To do this you must gain experience with these tradition-related harmonies by buying suits, trying on clothes, reading other people’s reviews of styles, reflecting on why you think a given person dresses well – as Derek also points out. In short, the path to good taste in clothing is, as in all other cultural fields: commitment and practice.

Get new posts by email