Derek from Die, Workwear writes at length about good taste in a recent article. I think I agree with him in several ways. For instance, he’s right that you can hardly define timeless, specific rules in dressing, including classic menswear. Alan Flusser, among others, has a somewhat unfortunate tendency to do so.

But I think Derek uses the sociological arsenal too one-sidedly, so he ends up reducing good taste to a mere act of social desire and positioning. Take Bourdieu, whom Derek uses as an analytical framework. The French sociologist certainly saw taste as a status symbol in class society. But not only. Bourdieu was aware that cultural fields over time develop knowledge and expressions that are not only socially finer than other knowledge and expressions, but may in fact be so. Mahler actually composes better music than Peter in the third grade!

If you take a field like classic menswear, it will also contain, in Bourdieu’s perspective, a real, transhistorical knowledge of dressing well. It is similar to what we call time tested. It could be, for example, colour use and cuts. It is difficult to carve out this knowledge, this good taste, because it is very context-dependent. Many people, like Flusser, get too ambitious here, when they try to specify rules. But anyone who has dealt with a field like classic menswear will recognise that some clothing styles are actually more successful than others, are better taste, because the mastery of basic tools like colours, fabrics and cuts is better. It’s like any other cultural field from theatre to carpentry to a new house. Some things are actually better, more beautiful than others, if you have a knowledge of the field. It is only from a distance that this exercise of taste can look like social positioning alone.

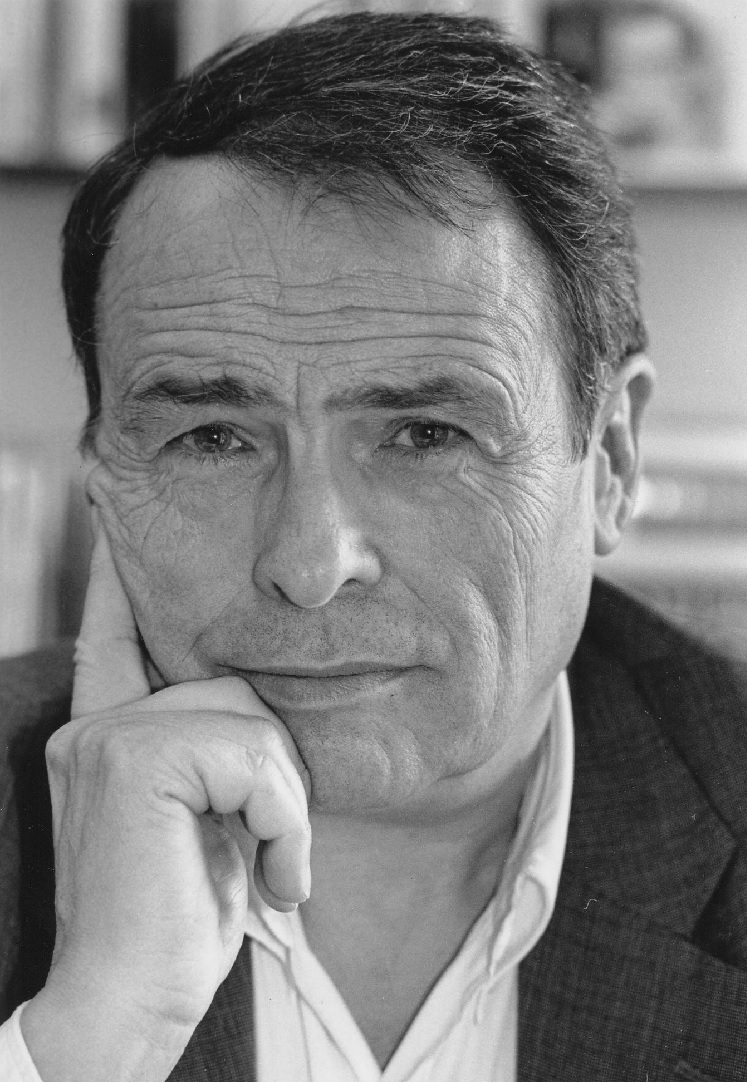

The Norwegian writer Knausgård has captured the experience of good taste in clothes very well:

“Christina always dressed beautifully, not ostentatiously, but unusually tastefully. It was not strange, she was a trained designer. I always looked at her clothes when we met, and it filled me with a kind of pleasure, perhaps it was the accomplished assurance that did it, how everything was coordinated, but without the coordination being visible, for that would have been a demonstration of well-dressing, and how the little details like a scarf or a belt brought out the best in the other parts, like lifted it up, while they themselves were in focus, for example a strong belt buckle, and in the background, as the strong helped to highlight the other. Colours, cuts, fabrics, patterns. Everything was coordinated from a certainty that could not be other than intuitive. It was something she knew how to do, and which she made no effort to create. In this, she was able to do something almost no one can do, which is to blur the differences between what was new and what was used, what was expensive and what was cheap, by disregarding those characteristics and seeing what the clothes or accessories were in themselves.”

Isn’t there a governing principle, a nomos in Bourdieu’s words, even in classic menswear? Yes, tradition/not tradition stands strong. For example, in the field of classic menswear, it is decidedly easier to dress successfully in a blue jacket and white trousers than vice versa, because the former combination is a well-established tradition. In addition, I see that harmony/not harmonious, in straight line from Beau Brummell, influences what is good taste. As a minimum requirement, we can perhaps say that a style in classic menswear must exhibit a tradition-conscious harmony of colors, patterns, fabrics, textures, cuts, make, and accessories in relation to a given body in order to establish itself as good taste.

To do this you must gain experience with these tradition-related harmonies by buying suits, trying on clothes, reading other people’s reviews of styles, reflecting on why you think a given person dresses well – as Derek also points out. In short, the path to good taste in clothing is, as in all other cultural fields: commitment and practice.

I entirely agree. While the concept of “timeless style” vs. “fleeting fashion” is undoubtedly overstated in CM circles, DW’s point seem to be that we’re just dressing up so?? so… dress up like people who dress up in the same genre ‘well’?

The subjectivist fallacy of aesthetics has, in my opinion, impoverished the collective sense of beauty, especially among those who’ve neither the talent nor inclination to work assiduously at some sort of personal style statement vibe.